PURPOSE-BASED BENCHMARKS

J. Gustafson

SUN MICROSYSTEMS, INC., USA

Summary

We define an approach to

benchmarking, Purpose-Based Benchmarks, which explicitly and comprehensively

measures the ability of a computing system to reach a goal of human interest. This

contrasts with the traditional approach of defining a benchmark as a task to be

timed, or as the rate at which some activity is performed. Purpose-Based

Benchmarks are more difficult to create than traditional benchmarks, but have a

profound advantage that makes them well worth the trouble: They provide a

well-defined quantitative measure of the productivity of a computer

system.

1 Introduction

Purpose-Based Benchmarks provide a means for assessing

computer productivity. The focus of this paper is the motivation and methods

for designing such benchmarks. Elsewhere in this volume, [Faulk et al. 2004] make use of this

benchmark approach as a core component of productivity analysis, and focus on

human factors analysis and the measurement of software life cycle costs.

1.1 BENCHMARK DESIGN GOALS

Benchmarks are tests of

computer systems that nominally serve two main purposes [Kahan 1997]:

1) to help potential users of systems estimate the performance

of a system on their workload, prior to purchase, and

2) to help system designers optimize their designs before

finalizing their choices.

Implicit in both of these is the idea that the

benchmark is low-cost or quick, compared to running a full customer workload

(or actually building a system.) However, some historical benchmarks have

ignored this common-sense aspect of benchmarking and have created tests that

cost many man-months of effort and over a hundred thousand dollars to run.

Ideally, benchmarks should maximize the amount of guidance they provide for the

least possible effort.

The most common aspect of a computer that benchmarks

test is “speed.” However, speed on a computer is not a well-defined measure.

Computer “speed” lacks the properties we demand of metrics in physics, like

meters per second or degrees Kelvin [Snelling 1993]. The reason is that

computer speed is “work” divided by time and computer “work” is not well defined.

The standard workaround for this is to attempt to define a fixed task as the

work, and consider only the reciprocal of the execution time as the figure of

merit that we call “speed.” Another common approach is to treat quantities like

“transactions” or “floating-point operations” or “logical inferences” as atomic

units of work that can be used as the numerator in the speed definition. However,

this approach fails because the quantities being counted vary greatly in

individual complexity and difficulty, and hence cannot be used as scientific

units.

1.2 THE BENCHMARK-WORKLOAD GAP

Every benchmark sets up an adversarial

relationship if the benchmark designer and the benchmark user are different

parties. Even if a test is used within a company to assess a proposed design,

the engineers are highly motivated to show that their choices yield favorable

results. However, the primary tension of benchmarking is between marketing

departments and potential customers. As soon as a benchmark becomes widely

used, the feature subset that it exercises becomes overvalued. This sets up a

dynamic in which the vendor can reduce its costs by neglecting parts of workloads

that are not tested by the benchmark, even though they might be quite important

to the customer.

One response to this is to create a large suite

of tests, in the hope that somehow every aspect of a workload is covered.

However, this raises the cost of running the benchmark, and might not succeed

in covering the total workload. SPEC and PERFECT Club are examples of efforts

at achieving general workload coverage through the amassing of program examples

that seem qualitatively different in some respect. It takes only slightly

longer for vendors to tune their offerings in such a way that they perform well

on these suites but not on applications in general.

The message here is one for the benchmark

designer: Assume people will exploit any difference between the benchmark and

the actual workload, because there will always be motivation to use a benchmark

not as a scientific tool but as a persuasion tool. Put another way, the

consumer of benchmark information thinks: “This only tests a subset of the

machine properties, but I can probably assume that the untested things are

similar in performance.” The benchmark measurer thinks: “This only tests a

subset of the machine properties, so I can sacrifice the performance of

everything that isn’t tested.” Both situations exploit the benchmark-workload

gap.

The following examples show the types of things

the author has watched go wrong in benchmarking because of the adversarial tension:

Example: A benchmark allows reporting of the best performance achieved, not the median

or mean. Therefore, the benchmark measurer runs it twenty times and manages to

find and report the rare case that performs 30% better than it does on average.

Example: A benchmark requires that 64-bit floating-point data be used throughout,

but only checks that the answer is correct to a few decimals. Therefore, the

benchmark measurer uses quick approximations for all of the intrinsic functions

like sin(x), ex, and log(x), each valid to only four decimal places, saving 20% of the run time.

Example: A benchmark states a large set of activities to perform, but only asks

that some of the results be printed or displayed. Therefore, the benchmark

measurer uses a compiler that tacitly eliminates any code that does not affect

the output, effectively “running” large portions of the benchmark in no time at

all.

Example: A small (kernel) benchmark, like many benchmarks, only measures the execution

time but not the time to create the executable code. Therefore, the benchmark

measurer uses a compiler that requires four days to exhaustively optimize the

kernel operation, and the program then runs in 11 seconds instead of 16

seconds. The benchmark measurer is further able to boast that no assembly language

or hand tuning was needed to achieve this 45% speed improvement.

Example: A benchmark measures both processor time and the time for I/O from disk,

and thereby captures the time for scratch I/O, the time to read in the problem

description, and the time to write out the final answer. But it doesn’t time

the ten minutes it takes to load the program into an 8000-processor system with

a poorly-designed operating system… so what’s claimed as a 14-minute run really

took 24 minutes total.

Example: A benchmark requires that only a single processor be tested. Therefore,

the benchmark measurer disables the processors in an eight-processor architecture

while leaving their caches and memory controllers active, allowing the entire

benchmark to fit into the local cache and run in half the time it would for any

configuration that a person would actually elect to use.

Example: A benchmark measures a standalone system, since the statistical effect of

other users who share the system seems difficult to incorporate into the

benchmark rules. So, a person who buys a system based on the standalone

benchmark is alarmed to discover that the system takes two minutes to roll one

task out and another task in, making the system far less productive in actual

use than the benchmark predicted. The system designers had no motive to make

context switching fast since they knew it was not measured by the benchmark.

Example: A benchmark based on an application program always uses the same input

data, even though the application program is capable of running a large range

of possible inputs. Therefore, after the benchmark has been in common use for

about three years, the benchmark measurers have learned to make that specific

data set run fast even though doing so has reduced the average speed for the

full range of possible input.

Specific names of institutions and people who

have employed these techniques are not given in these examples, because the

intent is not to assign blame. The intent is to illustrate how traditional

benchmark design inevitably leads to such distortions.

As the benchmark designers discover each of

these unintended consequences of their imprecise rules, they add rules to stop

people from abusing the test in that particular way. This is the approach of

the SPEC consortium, for example. Enforcement of such rules is difficult or

impossible in some cases.

A better approach is to define the benchmark

in a way that aligns with real computer use so closely, that “cheating” is no

longer cheating. Any method found to run a real workload faster or better is inherently a

legitimate design improvement and not a cheat. Where there is no gap between

workload and benchmark, no cheating is possible. Section 2 will describe this

approach in detail.

1.3 PRINCIPLES FOR REPORTING

RESULTS

The High-Performance Computing (HPC) community

is surprisingly lax in applying standards of scientific reporting. When a

scientific paper is published announcing an experimental result, the authors

expect to be held accountable for the validity of their claims. Yet, many HPC

benchmarks are reported with anonymous, undated database entries that are not

reproducible by third parties. If a clever technique is invented that allows a

higher score, the submitters are in many cases allowed to keep their technique

secret so that it becomes a competitive advantage; consumers of the data are

misled that one system is superior, when the superiority actually lies in the

cleverness of the programmer.

In general, we should demand

the following of any benchmark report:

1) The date the test was made

2) Who ran the test and how they may be contacted

3) The precise description of what the test conditions

were, sufficient that someone else could reproduce the results within

statistical errors

4) The software that was used, and an explanation for any

modifications made to what is generally available as the definition of the

benchmark

5) An accounting of cost, including the published

price of the system and any software that was used in the run.

6) An accounting, even if approximate, of the amount of

time spent porting the benchmark to the target system.

7) Admission of any financial connections between vendor

and the reporter; was the system a gift? Do they work directly for the vendor

or for a contractor of the vendor?

8) The range of results observed for the test, not just the

most flattering results. The reporters should reveal the statistical

distribution, even if there are very few data points.

The last several requirements go beyond the

reporting needed for scientific papers. They must, because of the direct

marketing implications of the reports. Scientific papers usually don’t imply

purchasing advice, the way benchmark reports do. The bar for benchmark reporting

must be even higher than it is for scientific publishing.

1.4 A MINIMAL REPRESENTATIVE SET

Benchmark suites tend to grow beyond the size

they need to be, for the simple reason that users refuse to believe that their

requirements are represented unless they see a part of the suite that uses

their same vocabulary and seems superficially to resemble their own workload.

Thus, a program for finding the flow of air

around a moving automobile might solve equations very similar to those of a

weather prediction model, and use the same number of variables and operations,

but the automotive engineer would refuse to accept a weather benchmark as

predictive. Thus, benchmark components proliferate until they become almost unmanageable.

When the underlying demands of a workload are

analyzed into machine-specific aspects like cache misses, fine-grain

parallelism, or use of integer versus floating point operations, applications

look even more similar than one might think. For example, even “compute-intensive”

problems rarely contain more than 5% floating-point operations in their instruction

traces, and 2% is typical. [IBM 1986] Our intuitive prejudice that each

technical application area deserves its own operation mix may not withstand scrutiny.

The more profound differences that need to be

representative are things like problem size. In circuit design, for

example, 95% of the work might be small jobs that run in a few minutes and

easily fit into a 32-bit address space; but the other 5% involve full-chip

simulations that require 64-bit addressing and a very different set of system

features to run well. Yet, both are in the “EDA market.”

To use a transportation analogy, the difference

in performance of two cars in commuting a distance of 20 miles is not apt to be

very great, and probably does not depend that heavily on the city for which the

commute is measured if the cities are about the same size. However, imagine the

time to commute into a town of 2000 people being used to predict the time to

commute into a town of two million people. It’s patently absurd, so we know better than

to lump those measures together into a single category called “commuting workload.”

Getting the problem size right is perhaps the

most important single thing to match in using a benchmark to predict a real

workload. This is especially important in the HPC arena. Yet, it is usually the

first thing to be thrown out by benchmark designers, since they want a small

problem that is easy to test and fits a wide range of system sizes.

1.5 BENCHMARK EVOLUTION

1.5.1 Activity-Based Benchmarks. For decades, the benchmarks

used for technical computing have been activity-based. That is, they select certain

operation types as typical of application codes, then describe an example of

those activities with which to exercise any particular computer. When accuracy

is considered at all, it is not reported as a dimension of the performance.

Current examples include

STREAM: Measure the time for simple vector operations

on vectors of meaningless data, of a length chosen to exercise the main addressable

memory. Assume answers are valid. The activity measure is “bytes per second.”

Confusion persists regarding whether distributed memory computers are allowed

to confine their byte moves to local memory [McCalpin].

GUPS: Measure

the rate at which a system can add 1 to random locations in the addressable memory

of the computing system. The activity measure is “updates per second.”

Confusion persists regarding whether distributed memory computers are allowed

to confine their updates to local memory, and the level of correctness

checking. While the latest official definition is the RandomAccess benchmark,

this definition is quite different from TableToy, the original benchmark that

measures GUPS.

LINPACK: Measure the time to use a

1980s-style linear equation solver on a dense nonsymmetric matrix populated

with random data. Measure answer validity, but discard this information in

reporting and comparing results. The activity measure is “floating-point

operations per second.” [Dongarra]

The inadequacy of these activity-based tests

for tasks (1) and (2) above is obvious. Neither the activities nor the metrics

applied to them have anything to do with actual user workloads. Their only

merit is that they are very easy to run. Scientists and engineers understand

that these are simply activity rates, but many take it on faith that activity

rates correlate with the ability of the computer to help them solve problems.

The LINPACK benchmark, which survives mainly as

a “Top 500” ranking contest, uses rules that place the measurement of activity

above the measurement of accomplishing a purpose. We now have methods for solving

linear equations, based on Strassen multiplication, that run in less time and give results that are more

accurate. However, the maintainers of the LINPACK rankings explicitly forbid

Strassen methods, because Strassen methods invalidate the floating-point

operation count. That is, the activity measure uses the older Gaussian

elimination method to determine the operation count. Strassen methods require

fewer operations to get the answer. Getting better answers faster via a better

algorithm is a violation of LINPACK rules.

1.5.2 Application

Suite Approach. In an effort to make benchmarks more representative than these small

kernel operations, benchmark designers have collected existing application

programs and packaged them as benchmarks [SPEC, Pointer 1990]. This packaging generally

includes:

1) Insertion of timer calls so that the program times its

own execution. (“Execution” does not include the time to compile the program or

load it into a system; sometimes it does not even include the time to load

initial data from mass storage or write the answer to mass storage.)

2) An effort to restrict the source text to the subset of

the language likely to compile correctly on a wide range of commercial systems.

3) A set of rules limiting what can be done to obtain

flattering timings.

4) A collection of results from other systems to use for

comparison.

5) A specific data set on which to run the application,

usually selected to be small enough to fit on the smallest systems of interest

at the time the benchmark is declared.

There is usually little attention to answer

validity [Kahan 1997]. Sometimes an example output is provided, and the person

performing the run must examine the output and decide if the answers are “close

enough” to the example output to be acceptable.

1.5.3 Accommodation

of New Architectures. As parallel computers such as the Thinking Machines CM-1, Intel iPSC, and

nCUBE 10 became available as commercial offerings, users found existing benchmark

approaches inadequate for prediction and comparison with traditional architectures.

Users and designers alike found themselves retreating to raw machine

specifications like peak FLOPS and total memory, since those metrics were

determinable and applied as systems scaled from uniprocessors to thousands of

processors.

In making the “application suite” benchmark approach

apply to parallel systems, one is immediately faced with the question of how to

scale the benchmark without losing the experimental control over what is being

compared. Obviously, larger systems are for running larger problems; however,

application suites invariably fix the size of the problem and have no way to

compare the work done by a large system with the smaller amount of work done by

a small system

The NAS Parallel Benchmarks are typical in this

respect; every time they need a different benchmark size, they must produce a

new set of sample output to use as the correctness test [Bailey and Barton,

1991]. This means the NAS Parallel Benchmarks are not, in fact, scalable. They

are simply different benchmarks available in different sizes. The new

architectures demanded scalable benchmarks where the “work” could be fairly defined

and measured.

1.5.4 Attempts

at Algorithm Independence. In the early 1990s, technical benchmarks were introduced that showed

alternatives to activity-based benchmarking, and allowed true scaling of the

problem.

SLALOM [Gustafson et al., 1991] had a kernel similar to

LINPACK, but fixed the execution time at one minute and used the amount of

detail in the answer (the number of patches in the domain decomposition for a

radiosity computation) as the figure of merit. It was language-independent,

allowed any algorithm to be used, and included the time for reading the problem

from mass storage, setting up the system of equations, and writing the answer

to mass storage. It was the first truly scalable scientific benchmark, since

the problem scaled up to the amount of computing power available and was

self-validating.

SLALOM had a fatal flaw: The test geometry was

symmetric, and researchers eventually found ways to exploit that symmetry to

reduce the work needed compared to the general case. The rules had failed to

specify that the method had to work on a general geometry. The definition of

answer validity (answer self-consistency to 8 decimal digits) was better than

previous scientific benchmarks, but still arbitrary and not derived from real

application goals. The lesson we learned from this was the need to subject

algorithm-independent benchmarks to extensive preliminary review by innovative

people before releasing the benchmark definitions for general use.

The HINT benchmark [Gustafson and Snell, 1995]

finally established a rigorous figure of merit: The accuracy of a numerical

integration. HINT scales to any size without needing comparison against a pre-computed

answer set. By defining the purpose instead of the activity (“Minimize the

difference between the upper and lower bound of the area under a curve”), a

level playing field was finally created for fair comparison of vastly different

computer systems. The person using the benchmark can use any numerical

precision, floating point or integer type. Version 1.0 of HINT is still in use;

it has remained valid through six cycles of Moore’s law and shows no sign of

needing redefinition. Its only shortcoming as a benchmark is that the problem

it solves is of little human interest.

1.5.5 Grand

Challenges, ASCI, and HPCS. During the 1990s, the discrepancy between HPC benchmarks and federal

program goals became too great to ignore. The “Grand Challenge” program for

supercomputing was so lacking in precise goal measures that it experienced a

loss of congressional support for funding [Weingarten 1993, Gustafson 1995].

The ASCI program set a goal of a “100 teraflops computer by 2004,” repeating

the assumption that peak floating-point activity rate, by itself, closely

predicts the ability to produce useful physical simulations. The emphasis on

floating-point speed created a generation of large computing systems that had

high arithmetic speed but were unreliable, hard to use, and hard to administer.

Recognizing this, in the early 2000s DARPA developed

a program, High Productivity Computing Systems (HPCS), to re-emphasize all

those aspects of computer systems that had been neglected in the various giant

computer projects of the previous decade. DARPA recognized that existing

benchmarks were incapable of holistic productivity measurement, and made the

development of new and better metrics a key goal of the HPCS program.

The next step in benchmark evolution became

clear: Can we create benchmarks that have rigorous definitions of progress

toward a goal of real human interest, so that they can measure the actual productivity of

computer systems?

2 Purpose-Based

Benchmarks

2.1 DEFINITION

A purpose-based benchmark (PBB) states an objective of

direct interest to humans. For example, “Accurately predict the weather in the

U.S. for the next three days” is a starting point for a more precise description

of something to be done, and a complete PBB supplies both English and

mathematical definitions of the task and the figure of merit. It does not tell how to accomplish the

task with a computer, leaving the benchmark measurer free to use any means

available. Whatever technique is used, however, must be supplied in such a way

that any other benchmark measurer could use that technique if they wished, or

else the benchmark results are not considered valid and publishable.

For those who wish to test a computer system

without testing the program development effort, a PBB provides a set of reference

implementations. This is simply to allow people to focus on the execution performance

if they wish to ignore program development effort. It is very important that

the productivity of a novel architecture not be measured starting from an

inappropriate reference implementation. If a system demands a starting point

that is not similar to one of the reference implementations, then the time to

develop an appropriate starting point must be measured separately as program

development effort.

The hardest part of designing a PBB is to find

a quantitative measure of how well a system achieves its purpose. The

floating-point arithmetic used in scientific calculations yields different

answers depending on the algorithm, the compiler, and the actual precision in

the hardware (including registers with guard bits). Given this, how can we

fairly compare completely different algorithms and architectures?

In the weather example, we can compare against

physical reality. Where this is impractical, we seek tasks for which the

quality of the answer can be calculated rigorously by the computer itself. In

both cases, methods such as Interval Arithmetic can play a key role by measuring

the uncertainty in the answer [Hansen and Walster, 2004]. This is in contrast,

say, to measuring problem quality by the number of grid points; adding grid

points does not always increase physical accuracy in simulations. We are

accumulating problems for which both the physics and the solution method are

sufficiently rigorous that the answer can be bounded or self-checked, because

that provides a quantitative measure of how well a program meets its purpose.

Note that the PBB approach can measure

productivity using legacy codes and does not require a completely new program

to be written, for those problems where a quantitative measure of answer

quality can be rigorously defined. The primary departure from the conventional

use of legacy codes as benchmarks is that one must measure aspects other than

just the execution time. For example, a PBB statement for electronic design

might be to design an n-bit adder and test it, with the purpose of making the circuit fast, small,

and provably correct. Users of electronic design codes do not mainly write

their own software, but obtain it from independent software vendors. Hence, a

PBB for electronic design could compare existing software packages to see which

one results in the best productivity for the complete task of designing the

adder.

Making data-specific tuning is obviously

impossible in the case of predicting the weather. Note that there is no need to

state what kind of arithmetic is used (like 64-bit or 32-bit floating point),

since any arithmetic that accomplishes the purpose is legitimate. Benchmark

measurers are encouraged to be economical in the activity performed by the

computer, so doing more operations per second is no longer a goal in itself. In

fact, aiming for more operations per second might lower the score on a PBB

because it leads one to use less sophisticated algorithms [Gustafson 1994].

2.2 ACCEPTABILITY FUNCTIONS

The concept of Utility is defined in game theory

[Luce and Raiffa, 1957]. It is a scalar ranging from –ī to +ī that

attempts to quantify the value humans place on outcomes so that different

strategies can be compared. We use a related concept here, that of Acceptability. The Acceptability

Function of

an aspect of a computer system is the fraction of users (in a particular

field) who deem the system acceptable. Unlike Utility, Acceptability ranges from 0 to 1.

Acceptability Functions were first proposed as a way to give quantitative

meaning to the vague goals of the U.S. “Grand Challenge” computing program [Gustafson

1994].

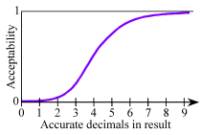

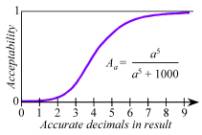

Acceptability Functions

quantify the nonlinearity of the utility of many computer features. For

example, if one computes Ļ, having only one digit of accuracy in the result is

unacceptable for most applications; six digits might suffice for most

applications, but 60 digits of Ļ is seldom worth ten times as much to a user as six

digits! The Acceptability climbs from near zero (unacceptable) for single-digit

accuracy to near unity (completely acceptable) for six or seven digits of accuracy.

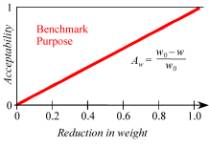

Figure 1. Acceptability Function Example

Here are some qualities of

computer systems that are amenable to Acceptability function analysis:

• Reliability (fraction of runs that complete satisfactorily)

• Availability (fraction of the time that the system can be used

for the problem)

• Precision (relative or absolute accuracy of the results)

• Time to port or develop the application

• Time to boot the system from a cold start

• Time to load the system with the application

• Time to execute the application

• Acquisition cost of the system

• Operational cost per hour of the system (or cost of each run),

including all administrative costs

• Space required (footprint or volume) for physical system

• Power required and heat

dissipated

For all of these aspects, each user has numbers

X and Y for which they will say

“Worse than X is unacceptable. Better than Y and we don’t care.” Instead of guessing about those

numbers, or letting them be implied and unstated, we can declare the

assumptions for each application area and let users in that area debate their

correctness. If a user says “The cheaper your system, the better,” he has

implied a linear utility for the system cost and a lack of concern, say, with

reliability.

There’s an old saying in marketing: “Fast,

cheap, and good… pick any two.” We can actually give this idea serious

treatment by requiring that łAi be at least, say, 0.9 for all the Acceptability

functions Ai. If computer procurements were stated in such terms, there would be much

better communication of requirements between users and system designers.

The aforementioned problems with repeatability,

time to compile, reliability, time to load, and so on, can all be incorporated

into an Acceptability Product. The Acceptability Product is the product of the Acceptability

Functions. If a particular aspect is more important, then it can be given

greater weight simply by making its function steeper or altering where it

changes from 0 to 1.

What traditional benchmarking does not take

into account is that this nonlinearity applies to execution time… and that the Acceptability

curve varies widely from one application area to another. In fact, one might

define a technical computing market as a collection of customers with similar

Acceptability curves as well as similar workloads.

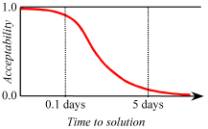

High-energy physicists have a culture of planning

large-scale experiments and waiting months for the results. In using supercomputers to

test the viability of theories (like quantum chromodynamics, or searching for

rare events in acquired data), they show similar patience and are willing to

consider computer jobs requiring months to complete. If given more computing

power, they would almost certainly escalate the problem being attempted instead

of doing the same task in less time. If they don’t, other scientists with more

patience will make the discoveries first.

The 24-hour weather forecast must be completed

and submitted in three hours, in practice. Forecasters have found that the

effort to update or extrapolate stale input data becomes so arduous at some

point that a 24-hour forecast would never finish or would be too inaccurate to

be useful.

In military applications, like using a computer

to determine whether a tank is that of a friend or a foe, any time longer than

a few seconds might be fatal. On the other hand, there is little difference

between taking 0.2 second and 0.1 second to compute, since human response time

is then greater than the computing time.

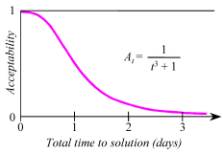

The following is a possible Acceptability

function of execution time, for a particular application area:

Figure 2. Time Acceptability Example

This leads directly to the question of whether

a benchmark has to last the same amount of time as the actual workload, in

order to be representative and have predictive value. If the only way to

predict the performance on a ten-month-long physics run is to test the machine

for ten months, then the benchmark itself is prohibitively expensive and

becomes useless in such situations. Whereas business applications quickly reach

steady-state behavior that permits accurate sampling, many technical

applications progress through phases that make highly varying demands on the

system hardware and software. It is not simply a matter of “warming the cache”

in some cases. Therefore, any simplification of HPC workloads must be validated

scientifically to show that the reduced problem produces results that correlate

with the actual workload.

2.3 EXAMPLE: PBB FOR STRUCTURAL ANALYSIS

(TRUSS OPTIMIZATION)

We now bring all these measurement principles

to bear in a benchmark designed to capture the workload of engineers who use

computers to assist in structural analysis [Mullen and Muhanna, 1999]. Typical

problems in Mechanical Computer-Aided Engineering (MCAE) are

• Find the stresses and strains in a design to see if it meets

requirements.

• Optimize a design for a particular feature, like low weight or

low cost or high efficiency.

• Find out if the design has resonant modes that could cause

failure when shaken (buildings, bridges, engines, etc.)

This motivates the purpose of the benchmark problem.

We also pay attention to the other aspects of this segment that determine the

other Acceptability functions. Answer validity is of extreme importance,

because failures may lead to loss of life or many millions of dollars in

damage. Hence, the cost acceptability function is related to the amount of

damage (and losses from lawsuits) that the computer can prevent. Also, note

that in the design of a large structure, the position of the parts probably

must be specified to a precision comparable to other sources of errors in the

part manufacturing and assembly. For example, 0.1 millimeter is probably overkill

in a large structure, and 60 millimeters is probably out of tolerance. Finally,

we note that mechanical engineers are accustomed to waiting several hours for

an answer, even overnight, which is still not such a long time that it delays

the construction of a proposed mechanical object. This takes into account the

trial-and-error time needed, not just a single static solution for a proposed

design.

This is the basis for the “Truss” benchmark, which

we now define. It is clearly far simpler and more specific than the gamut of

mechanical engineering tasks, but it appears representative of much of the

workload.

2.3.1 English

Statement of Purpose. Given a set of three attachment points on a vertical surface and a point

away from the surface that must bear a load, find a pin-connected steel truss

structure that uses as little steel as possible to bear the given load. The

structure must be rigid, but not overdetermined. Cables and struts vary in

thickness based on the forces they must bear, including their own weight and

the weight of the connecting joints. Start with no added joints, which defines

the unoptimized weight w0:

Figure 3. Initial Truss Problem, No Extra Joints

The attachment points vary from

problem to problem. The system does not know the attachment point coordinates

until the run begins. The point in space where the load is located, the amount of the load, and

the strength of the steel (tensile and compressional failure) are similarly

subject to variation so that the benchmark cannot be “wired” to a particular

data set.

2.3.2 Mathematical Problem Formulation. The benchmark is not intended

to test the structural analysis expertise of a programmer; the complete

definition supplies the explanation that a “domain expert” in MCAE might supply

a programmer to enable the Truss program to be created.

The force equilibrium requirement gives rise to

a set of linear equations. The Truss PBB uses a “free body” approach. It does

not require finite element analysis. However, it produces equations that have

very similar structure to those used everywhere in structural analysis

(positive definite, symmetric, sparse).

The net force on every joint must be zero, or

else the truss would accelerate instead of being at equilibrium. (The vertical

surface, being fixed, will supply a countering force to anything applied to

it.) The weight of each member produces an additional downward force that is

split evenly between its endpoints.

These principals, plus formulas for the

strengths of struts and cables, complete the information needed to create a

working Truss optimization program.

2.3.3 Parallelization

Strategies. There

is enough work in Truss to keep even a petascale computer quite busy for hours,

because the set of possible truss topologies grows very rapidly with the number

of joints.

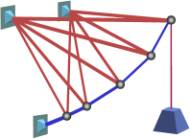

Figure 4. Parallel Topology Optimization

The outermost level of

parallelization is the topology generation. Even a small number of joints

generates billions of designs to test. The next level is the optimization of

any given topology, each of which can be spread over a large set of process

threads. The innermost level of parallelism is that of solving the sparse and

relatively small set of linear equations. This solving is iterative because

once the thickness of each truss or cable is determined from the applied

forces, the resulting weights must be used to recompute the load until the

solution converges. Interval arithmetic can be used to exclude certain

topologies or joint positions, and this exclusion needs to be communicated to

all processors so that future searching can be “pruned” [Hansen and Walster,

2004]. Load balancing and constant global communication create a representative

challenge for large-scale scientific computers.

Figure 5 shows a truss that

was optimized by an early form of this PBB. The blue lines represent struts (compressive

load), and the red lines represent cables.

Figure 5. Optimized Truss Structure

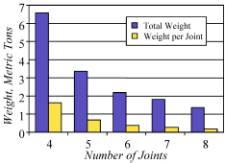

The weight reduction possible by adding

complexity is dramatic, lest anyone think that all this computing is

unnecessary. Figure 6 shows the drop in weight of the truss as joints are

added, using a topology similar to that shown in Figure 5.

Figure 6. Weight Reduction with Complexity

2.3.4 Acceptability Functions. The most important Ai are the ones that show

Acceptability as a function of the reduction in weight, the accuracy of the

answer, the time to perform the run, and the cost of the computer run. Many

others could be included, but let’s start with these.

The initial guess is to connect single beams

and cables from the attachment points to the load point. This is the heaviest

solution and easy to compute, so it defines the starting value. If we are

unable to reduce the weight, the Acceptability is zero. If we could by some

incredibly ingenious method reduce the weight to nothing (a sort of gossamer

structure), then Acceptability would be one. The purpose that defines this purpose-based

benchmark thus becomes one of the Acceptability functions. Acceptability = (Reduction

of weight) divided by (Initial weight). This is a simple linear function of the

weight w

and the unoptimized weight w0:

Aw = (w0–

w)/w0:

Figure 7. Truss Benchmark Purpose

Acceptability Function

We can estimate the

Acceptability function for the accuracy of the answer. This function and the

ones that follow are purely for purposes of illustration, and the function is

an invented one that “looks right”; it must be replaced by one based on actual

studies of user requirements. For now, it serves as a number the computer can

calculate at the end of a benchmark run, using higher-quality (and slower)

arithmetic than was used during the run:

Figure 8. Accuracy Acceptability

The time to perform the run

captures the patience typical of practitioners in this application area, which

is often dictated by the time required for the entire task. The actual construction

of a truss might require a few days to a few weeks, for example, so few

engineers would care about the difference between an instantaneous answer and

one that required, say, 15 minutes of computation. It is typical for structural

analysis programs to be adjusted in complexity to the point where a job started

at the end of the business day is finished by the beginning of the next

business day… about 15 hours. A run of less than 7 hours might be well accepted

(since it allows two runs per business day), but acceptance might drop to less

than 0.5 if a run takes an entire day. The following curve was constructed to

fit these estimates.

Figure 9. Acceptability of Solution Time

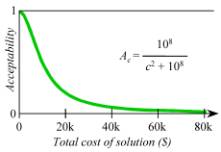

The cost of the run similarly

yields a decreasing Acceptability function. At first, the cost would appear to

be tied simply to the cost of the steel that is saved, which is probably only a

few thousand dollars. However, a characteristic of the structural analysis

segment is that the computation insures against a design failure that could

cost lives or result in catastrophic destruction of property. No one would

consider insuring a truss structure that had been designed without a quantitative

analysis regarding its strength and safety, because failure could cost millions

of dollars in lawsuits. The reasoning is similar to that used by actuaries to

determine the cost of liability insurance.

It is conceivable that some small fraction of

designers would be willing to spend over $50,000 to certify that a structure

meets all safety requirements while optimizing some aspect of the design. At

the other extreme, it may be petty to reduce the cost of the computer run

below, say, 0.1% of the cost of actually building the structure. Here is an

example of a possible Cost acceptability function:

Fig. 10. Acceptability of Cost

There are other Acceptability

functions that could be put into the Net Acceptability product, such as reliability

(fraction of runs that complete successfully), but we stop with these four for

now: A = AwAaAtAc.

This is a radical departure from the typical

way that cost and time are incorporated into benchmark reporting. Many

productivity measures use ratios to cost or ratios to time. This approach makes

more sense for traditional business computing, where cost and time are accurately

regarded as linearly disadvantageous. Taking twice as long or costing twice as

much is clearly half as productive for a given amount of output. This is much

less the case for high-end, technical computing.

2.3.5 Result Reporting and Verification. The Truss benchmark produces

an output that would be sufficient for an engineer to create the structure: the

list of joints, their position in space, the members that connect to them,

whether the members are cables or struts, and the length and cross-section of

each member. Since the input requirements have a random component to prevent

“cheating” on the benchmark, it is not immediately obvious how to verify that

the output is valid.

In addition to the output information listed

above, the benchmark requires that a list of forces impinging on each joint be

printed, and the sum of those forces. This makes clear whether the linear system was actually

solved, since the total force on every joint should be zero. The list of forces

is not so large that a human cannot scan it for validity, and of course, the

computer can easily compute the maximum deviation from zero of the list of net

joint forces as a single-value test of validity. We envision that the numerical

verification of the answer will use containment set methods that go well beyond

the arithmetic used to obtain the answer, and will be considered part of the

execution. These tests are in development at present.

2.4 OBJECTIONS TO THE PBB

APPROACH

The PBB approach was first presented to audiences in late 2002. Some of the

common reactions and responses follow.

You shouldn’t reduce

performance to a single number. It’s clearly a multidimensional quantity.

Yes, but if you don’t define a way to reduce it to a single number, someone

else will. Their summation probably will not be the one you envisioned. Therefore,

I strongly recommend that any benchmark present the multidimensional data and try to specify the single

figure of merit that best correlates with the way users would coalesce all

those values. Ultimately, people will reduce any collection of aspects to a

single number that determines whether they are willing to pay the price for the

system. The Acceptability Functions communicate what the assumed importance is

of each aspect of the system, but anyone can take the component measures and

apply their own set of Acceptability Functions to the same metrics. See [Smith

1988] for an in-depth discussion of the single-number reporting issue.

Since

the PBB rules are so loose, doesn’t that make it easy to cheat?

On the contrary, it makes cheating impossible by defining it away. Cheating

is possible only when there is a difference between user goals and what is actually

measured. In the ten years that HINT has been available, not a single method of

cheating has been found; this is for the reason stated. Imagine that someone

finds a way to “cheat” by predicting the weather more accurately with less

effort. How could that possibly be considered cheating? If some discrepancy is found between the user goals

and what the PBB measures, then the PBB is simply redefined to eliminate the

discrepancy.

You

have to be a real domain expert to use one of these things.

Not if we do our job right. While we need a domain expert to construct the

benchmark (and supply Acceptability criteria), understanding a PBB description

shouldn’t require a specialized degree in mechanical engineering or finance or

meteorology to understand. Both the purpose and the explanation of how to solve

the problem should be accessible to the educated public. The Truss benchmark,

for example, requires only high school physics to program once we provide the

rules for the strength of the cables and struts. Most of these problems require

a one-page lesson in the specific math and physics they require, but if they

require more than that, we probably have an unusable PBB and should redesign

it.

Doesn’t this just measure

the cleverness of the programmers instead of the system? What will happen if

someone comes up with a very clever way to solve the problem?

Whatever clever method is used, it must be shared with everyone as part of

the reporting of the benchmark. Others can then choose to use the technique or

not. Furthermore, since PBBs can (and should) take into account the development

cost, the use of clever programmers or extensive tuning effort will show up as

reduced Acceptability in the development cost aspect.

I don’t see how to make

my workload purpose-based.

The PBB approach

doesn’t work universally; at least it doesn’t yet. An example of a workload

that is difficult to make purpose-based is: “Run a simulation showing two galaxies

colliding.” Checking the simulations against actual experiment could take a

long time indeed. There is no attempt to establish the accuracy of the answer,

since the value of the computation is the qualitative insight it provides into

an astrophysical phenomenon. While we acknowledge the importance of programs

for which the output is judged in a non-numerical way, we do not currently have

a benchmark approach that encompasses them.

Why multiply the

Acceptability Functions together? Wouldn’t a weighted sum be better?

A

weighted sum makes sense for many “productivity” definitions, such as each

stage in a software life cycle, but “acceptability” has different implications

as an English word. The reason for using products is that one unacceptable parameter means the entire system is

unacceptable. That’s

easier to do with products than with weighted sums. Imagine a system that is

affordable, fast, and easy to program, but has just one problem: It never gets

the right answer. Should that failure be thrown into a weighted sum as just one

more thing to consider, or should it be given multiplicative “veto power” over

the single-number rating? There may be aspect pairs that represent tradeoffs,

where poorness in one aspect is compensated by excellence in another, and then

a weighted sum would be the right model. The Acceptability Product is similar

to what one sees in formal procurements for computer systems. The Acceptability

of the system is the logical AND of all the requirements being met, and not

expressed as tradeoffs.

I

have a computer program that solves a very interesting problem; can we make it

into a Purpose-Based Benchmark?

Many

people have presented the author with programs from their area of interest and

suggested that they be used to define a PBB. The usual obstacle is that there

is no quantitative definition of how well the program achieves its purpose, and

the person has no idea how to compare two completely different methods of

solving the problem that take the same amount of time but get different

answers. Once that’s done, the rest of the task of converting it to a PBB is

straightforward.

What you’re proposing is too difficult.

If what you

want to measure is Productivity, it’s difficult to see how it can be made simpler.

2.5 FUTURE WORK

One lesson from history is that benchmark definitions are

difficult to change once they are widely disseminated. Hence, we are doing very

careful internal testing of the PBBs before including them as part of a published

paper. We are testing the Truss PBB with college programming classes right now.

We will create versions in various languages and with various parallelization

paradigms (message passing, global address space, OpenMP) to use as starting

points for those who wish to test just the execution characteristics of a

system. Once these have had sufficient testing, we will disseminate them

through the Internet and traditional computing journals. While the temptation

was great to include an early version of a code definition of Truss in an

Appendix, this would almost certainly result in that becoming the community

definition of the benchmark prematurely.

A second PBB that involves radiation transport is nearly

complete in its English and mathematical definition. An I/O-intensive PBB based

on satellite image collection, comparison, and archiving is under review by

experts. A weather/climate PBB consists almost entirely of defining the quality

of a prediction, and we expect to use existing public-domain weather models as

reference implementations instead of attempting to develop our own. We are well

along in the creation of a biological PBB based on the purpose of using

computers to find the shapes and properties of proteins.

For each PBB, we are finding domain experts to review the

benchmarks and verify that the workloads are representative and

give initial feedback on the Acceptability Functions. Eventually, the

Acceptability Functions should be determined by statistical survey of users in

particular application areas, and updated periodically. A third-party

institution such as IDC might be ideal for this task.

SUMMARY

The

Purpose-Based Benchmark approach represents the latest in an evolving series of

improvements to the way computer systems are evaluated. The key is the expression

of an explicit purpose for a computation, and a way to measure progress toward

that goal as a scalar value. They are particularly well suited to technical

computing because they solve the long-standing problem of comparing computers

that give “different answers” because of floating-point arithmetic variation.

Furthermore, the Acceptability Function approach provides a way to express the

nonlinearity of user requirements for aspects of the computation, including the

Purpose.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work would not have

occurred without the impetus of DARPA’s High-Productivity Computing Systems

program. By identifying the need for quantitative measures of “productivity,”

DARPA has advanced the state of high-end computing in new and far-reaching

ways. The author also wishes to thank John Busch, manager of the Architecture

Exploration group at Sun Labs, for tenaciously driving and supporting

approaches to computer metrics that enable breakaway system design.

AUTHOR BIOGRAPHY

John Gustafson received his B.S. degree from Caltech, and his M.S. and Ph.D. degrees

from Iowa State University, all in Applied Mathematics. He was a software engineer

at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, a senior staff scientist and

product development manager at Floating Point Systems, and a member of the

technical staff at Sandia National Laboratories in Albuquerque, NM. He founded

the Scalable Computing Laboratory within Ames Laboratory, USDOE, and led computational

science research efforts there for 10 years. He joined Sun Microsystems in

2000; he is currently the application architect for Sun’s HPCS work. His

research areas are High performance computing, Performance Analysis, Parallel

architectures, Numerical analysis, Algorithms, and Computer graphics.

REFERENCES

Bailey, D., Barton, J., 1991.

The NAS Parallel Benchmarks. Report RNR-91-002, NASA/Ames Research Center.

Dongarra, J., updated

periodically. Performance of various computers using standard linear equations

software in a Fortran environment. Oak Ridge National Laboratory.

Faulk, S., Gustafson, J,

Johnson, P., Porter, A., Tichy, W., and Votta, L., 2004. Measuring HPC productivity.

(This issue.)

Gustafson, J., Rover, D.,

Elbert, S., and Carter, M., 1990. The design of a scalable, fixed-time computer

benchmark. Journal of Parallel and Distributed Computing, 12(4): 388–401.

Gustafson, J., 1994. A

paradigm for grand challenge performance evaluation,” 1994. Proceedings of

the Toward Teraflop Computing and New Grand Challenge Applications Mardi Gras

’94 Conference, Baton Rouge, Louisiana. (http://www.scl.ameslab.gov/Publications/pubs_john.html)

Gustafson, J. & Snell, Q.,

1995. HINT: A new way to measure computer performance. Proceedings of the 28th

Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Vol. II: 392–401.

Hansen, E. & Walster, G.

W., 2004. Global Optimization using Interval Analysis, 2nd edition,

Marcel Dekker, Inc., New York,

“IBM RT PC Computer

Technology, 1986. IBM Form No. SA23-1057: 81.

Kahan, W., 1997. The baleful

effect of computer benchmarks upon applied mathematics, physics and chemistry. The

John von Neumann Lecture at the 45th Annual Meeting of SIAM, Stanford University.

Luce, R. & Raiffa, H.,

1957. Games and Decisions: Introduction and Critical Survey,” John Wiley & Sons,

Inc., New York.

McCalpin, J., updated

periodically. “STREAM: Sustainable Memory Bandwidth in High Performance

Computers,” (http://www.cs.virginia.edu/stream/)

Mullen,

R., and Muhanna, R., 1999. Bounds of structural response for all possible

loading combinations. Journal of Structural Engineering. 125(1): 98–106.

Pointer, L., 1990. PERFECT:

Performance Evaluation for Cost-Effective Transformations. CSRD Report No.

964.

Smith, J. E., 1988.

Characterizing performance with a single number. Communications of the ACM, 31(10): 1202–1206.

Snelling, D., 1993. A

philosophical perspective on performance measurement. Computer Benchmarks, Dongarra and Gentzsch, eds.,

North-Holland, Amsterdam: 97–103.

SPEC

(Standard Performance Evaluation Corporation), updated periodically. (http://www.specbench.org/).

Weingarten,

F., 1993. HPCC research questioned. Communications of the ACM, 36(11): 27–29.